By Devraj Agrawal

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Hinduism is one of the world’s oldest and greatest faiths, and it has been practised throughout the Indian subcontinent for a long time. It is a way of life deeply rooted in Indian history, culture, and custom. The term “Hindu” is derived from the word “Indus” and refers to the civilisation of the Indus Valley.

Samskara[1] is a phrase that many Hindus believe in and was derived from Hinduism. The Sanskara term is used in Hinduism to denote significant Hindu traditions and rituals. One of the meanings of Sanskara is to cleanse oneself physically and psychologically. In Hinduism, there are several ceremonies such as-

When a woman is pregnant, a ceremony called Garbhadhana is done to ensure the health of her unborn child.

Namkarana is a new-born infant naming ritual.

When a kid is ready for formal education, he or she is called Vidyaarambha

Lavish nuptial ceremony- Vivaha

Antyeshti- last rites of passage or Hindu corpse ceremonies done after death

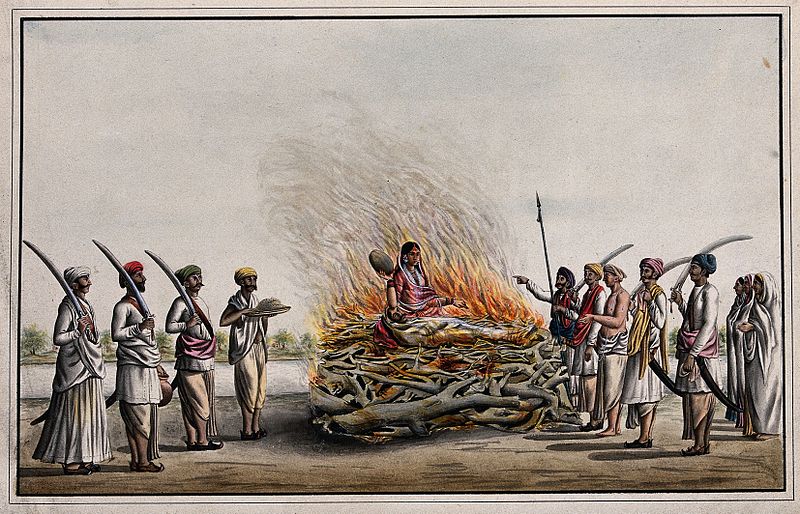

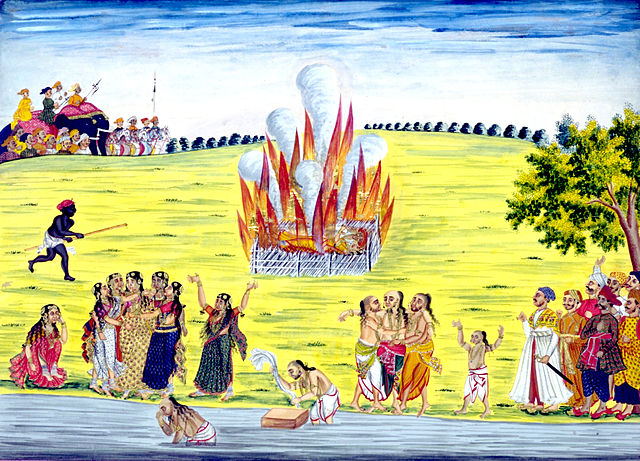

Sati is a component of Antyeshti, the last ritual. Sati custom holds that the wives wash their sins and misdeeds by entering the funeral pyre with their husband’s remains. Sati gives women opportunity to thrive in society. Stridharma for women implies devotion to one’s spouse; a husband for women is desired of god for her; and the Sanskrit term for “husband” is “swami,” which literally means “lord and master,” and the husband is himself lord for her and husband (Pati) as well. Sati is still regarded positively by some Hindus today.[2] Pativrata is devotion to spouse, and after he dies, she goes in the burning fire of husband as a devotion, and women who do the same are known as Sativrata. This devotion raises her to goddess status, deserving of worship. The dilemma here is whether Sati is a good wife since her devotion turns her into a Sati goddess. Is she a goddess worthy of worship? Is it all about making money for the family and the village?

1.2 ABOUT THE RESEARCH PAPER

This article follows the history of sati practise from its inception to its abolition, attempting to explore religious taboos, practises, and attempting to maintain human values, particularly those of women, in societal situations. This isn’t simply a storey; it’s also too instructive, jolting all sensible brains out of their slumber.

1.2.1 Research objectives

- To preserve human principles, especially those of women, in social situations. It is said that “man is the crown of creations” when it comes to living a healthy and happy life. This is not simply a slogan; every member of society must live with understanding, fraternity, and patience in the face of all religious laws, taboos, and rites.

- To discuss the history of the Sati practise and its religious beliefs among Indian Hindus. In addition, we shall examine the perspectives and thoughts of Indians and British people about Sati.

- To understand the historical context of Sati customs by examining various empires and dynasties.

- To comprehend the cultural and religious influences on women that lead them to sacrifice their lives.

- To examine the present situation of Sati practise and its legality.

1.2.2 Research Methodology

In this research report, the doctrinal technique of research was applied to approach the aforementioned subject. It is a source-based research that draws its content from both classic and current written text sources such as books, journals, and e-resources. This method is both analytical and descriptive in nature. The researcher has put a lot of effort to critically investigate all sources in order to present an informative and perceptive analysis. Opinions of research researchers, academicians, and other specialists who have dealt with this subject have been incorporated as a genuine contribution to this study.

1.2.3. Review of literature

Sati practice is being followed from centuries in the name of ritual to stop this inhuman practice was need of the hour and socialist had taken a lot many measures to eradicate the practice, various article has been published by scholars, historian and researchers to give us complete idea of sati pratha and spread awareness to stop the practice, various texts such as,”, Mahabharata, garud puran mentioned about sati “. The motive of this research paper is to highlight the reality and present the facts with reference to different secondary sources

1.2.4 Hypothesis

Sati has started long time back and as time passed this ritual has been wrongly interpreted by people and ritual turned into an unethical practice. Various kings, dynasty tried to abolish sati pratha and were successful to some extent, then measures has been taken by social worker and British government and made it unconstitutional. Today practicing sati is illegal and number of women following it has reduced drastically but still it’s not completely abolished.

2.1 MEANING, EMERGENCE AND ORIGIN OF SATI TRADITION

Sati (often called “suttee”) is a ceremony that entails burning a woman alive with her husband’s dead body; dying alongside her husband’s death in the same fire is considered the wife’s responsibility in this ritual. The genesis of Sati is a controversial issue among researchers because of contradictory facts. Hindus, on the other hand, see it as a sacred rite since numerous Hindu religious literature have addressed Sati practise and its afterlife benefits, either openly or implicitly.[3]

According to some scholars, Sati was the first woman to intentionally burn herself. Sati is derived from the name of the goddess Sati, who was the first woman to commit suicide by immolating herself. Because the father of goddess Sati was having issues with his daughter and the husband of sati deity Shiva, he did not invite them both to an important festival. When Goddess Sati learned about it, she went to face her father, but he mocked her spouse, causing Goddess Sati to become furious and offended with her father. She couldn’t take the humiliation any longer and burnt herself alive in anger. Despite the fact that she was neither a widow or died alongside her husband, her death became an example of the commencement of the sati rite. In Hinduism, marriage is an unbreakable tie, and when a wife dies with her husband, it implies she will join him after death. As a result of the bride’s promise, she is obligated to stay with her husband for seven lives. It was also thought to be necessary since the Sati ceremony was seen to be a cleansing ritual for their sins and the sins of their family.[4]

The exact origin of the sati practice is uncertain, but experts believe it came about for two reasons: The first was to protect women from enemies who invade their territory, such as the Mughals who attack Rajput lands; When a Rajput military man was killed in action, his widow is said to have blown herself up on his stake to avoid falling into the hands of the Mughals. When they are defeated in battle, only the Rajput caste in Rajasthan commit mass suicide known as Jauhar. For example, at Ajit Singh’s funeral in Marwar Jodhpur in 1724, sixty-six women were burned alive, while eighty-four women were sacrificed after the death of Budh Singh, king of Bundi.The similarities between Jauhar and Sati are striking, with the difference that Jauhar is performed by Rajput widows at the end of a failed war, while Sati is performed by a Hindu woman of religious belief. She gains dignity and power while honoring her husband’s family. As a result of her honorable sacrifice, the widow was able to escape hatred and gain fame for herself and her family.[5]

Jorg Fisch provides an alternate theory for Sati’s origins in his book Journal of World History. He claimed that Sati’s origins should not be traced too far back in time. He argues it was a private issue in which lovers or spouses died together or followed each other into death, regardless of gender. He continues, “As society became aware of this ritual, it sought to regulate or limit it by merging it into a public ceremony and determining who could and could not die”.[6]According to Jorg and Dorothy, this ritual was practised not just in India but also in other regions of the world, including Greece, Egypt, China, Finland, and some American Indians. We may learn two things from the conversation. The first is that there is disagreement among experts concerning the origin of sati. Second, after the goddess Sati, who was the first person to practise sati.Sati was concerned with females dying with her husband. Some scholars believe it was a mandatory tradition, while others believe women do it voluntarily for their husbands. Many people say that sati isn’t referenced in Hindu religious books, and there’s no indication of it in these Hindu religious and holy writings.

2.2 STATUS OF WOMEN IN SOCIETY

Scholars felt that in the past, women had no presence in society apart from the framework of males, therefore the sati rite made sense to them. Families think that following the death of a spouse, the women may go astray; in Indian past, women were permitted to be the object of males. They had little freedom or rights, and religion and society exploited them. She was seen as a social burden.[7] Women were not allowed to remarry after the death of their husbands, but husbands were allowed to remarry if their wives died. Violence against women, as well as sexual and gender-based violence, are heinous crimes against women and girls, according to Sati. They are victims of ‘hate crimes’ merely because they are female. The standing of women in modern India has altered drastically. In current Indian culture, she has the same social, economic, educational, political, and legal status as males. Sati, child marriage, and the temple prostitution system are no longer as common as they once were. Women in today’s age, although being treated equally with males, do not desire such privileges. Rights like “Women are equal to Men” can only be found in texts.

2.3 “HISTORICAL BACKGROUND” AND SATI IN RELIGIOUS TEXT

The Vedas do not give us a clear picture of sati; instead, they give us some indications about what women should do once their husbands die. For example, the Rig Veda does not mention wife burning: “Let these unwidowed dames with excellent husbands adorn themselves with fragrant balm and unguent.” “First, let the dames go up to where he Lieth, decked with fair gems, tearless, sorrowless.”[8] This Shloka (verse) is about the widow, and it states that she should wear nice perfume and apply creams to her body, that she should not lament or cry, that she should be happy, and that she should go up to where her husband sleeps. This poem doesn’t mention burning in the fire much, but it does mention a wife visiting her husband’s funeral pyre.

However, “Atharvaveda” a religious text which is also part of Veda, Purana, Daksha Smruti and Agni puran talks in favour of Sati practice and accept that its moral responsibility of wife and both goes to heaven and always stay together if women practiced Sati. Another religious text, the Garuda Purana, states that if the deceased has hair on his body, his wife will live in heaven for as many years as the number of hairs on his body: “A Wife who dies in the company of her husband shall remain in heaven for as many years as there are hairs on his person.” This scripture also states that a woman practising Sati cannot be killed by fire: “When a woman burns her body with her husband’s, the fire burns her limbs only but does not torment her spirit”.[9]

Sati practise is also mentioned in the “Mahabharata” literature, where a daughter of the monarch and Pandu’s wife, Madri, did sati following Pandu’s death.[10] A separate holy scripture, “Devi Bhagavatam,” also mentions Pandu’s death. It states that once Madri, full of youth and beauty, was living alone in a secluded spot, and Pandu seeing her hugged her and died as a result of the curse. When the funeral pyre caught fire, the chaste Madri jumped into it and died as a Sati.[11] “One of the texts, “Vishnu Purana,” tells the storey of Lord Krishna’s wives who immolated themselves with their husband. Krishna’s funeral fire was entered by 8 of Krishna’s wives. Rukmini, their leader, embraced Hari’s body. Revati, who was also hugging Rama’s body, joined the burning pile, which was cool to her since she was in contact with her Lord. Hearing about these occurrences, Ugrasena and Anakadundubhi, together with Devaki and Rohini, decided to join the flames.[12]

Women have the right, according to “Brihaspati Smriti,” to choose whether to do sati and accompany her spouse or to live a virtuous life. Wife was considered half the body of husband, thus her choice to survive or practise sati was significant. Despite the fact that there is actual proof of sati practise in Hindu holy texts, many individuals do not believe in sati and argue that the passages are misunderstood. Some say that sati was optional and not mandatory for widows, and many experts believe that sati began to defend women from invaders.

2.4 “SATI IN MEDIVAL INDIA”

Sati was prevalent practise among the top Hindu castes in the 7th century, according to evidence uncovered. Many occurrences of sati were documented between 1057AD and 1070AD. When a king dies in the south, his palace attendants, ministers, and wives follow him to the afterlife, but sati was not a choice act since once ladies consented, it was hard to alter their minds. It was most visible during the reigns of the “Kakatiyas, Yadavas, Hoyasalas, Musunur Nayaks, Padma Nayaks, and the Reddy dynasty”. In the 14th century, the Vijayanagar Empire was dominated by sati.[13]

In 1847, the Nizam of Hydrabad prohibited sati, but it was unsuccessful since women continued to perform sati rituals. The Hindu and Nizam governments agreed to refrain from interfering with their religious practises. However, Nizam reprinted the Judgement, declaring that no woman shall die with her husband while practising sati. If relatives or family members think a widow is planning sati, they must alert a government authority in that region. Even after this decree was issued, evidence of women practising sati was uncovered. This is because cops in the region may not take this regulation seriously, and family members refrain informing about women immolating suicide after death of their husbands.[14] Sati was found in Telangana (present-day Hyderabad) and was particularly prominent in “Indur Elgandar, Medak Sirpur, Tandur, Tandur, Aurangabad, and the Bid Perbani dynasty”. During the mediaeval period in south India, Sati was mostly committed by royal families, aristocrats, and lower caste peasants. It was still practised by the elite class of Hindus in north India, such as Brahmins.

Sati was practised in nearly every region of Mughal India. According to Ibn Batuta, Terry, and Pelsaert, it was not mandatory to immolate with one’s husband. According to Sidi Ali Reis, women were not forced to perform sati in Muslim areas. Nonetheless, Akbarnama states that sati, an ancient Indian ritual of widow immolation, may be involuntary as well. When Delhi sultans arrived in India, they did not meddle with Indian tradition. However, Mohammed bin Tughlak was the first Muslim ruler to speak out against sati. He made it mandatory to get a licence to burn widows, but he took no steps to totally outlaw sati. After him, Mughal emperor Humayun was the first to take significant steps toward the abolition of sati; after him, Akbar ended forced sati practise in his realm; and even Jahangir and Shah Jahan were in favour of sati abolition but were not fully successful in eradicating it. Finally, Aurangzeb prohibited sati practise in his kingdom, although he was unable to do so permanently. Many Muslim rulers attempted to save widows via various ways and were successful in many, if not all, of their endeavours, saving many widows.[15]

2.5 SATI TRADITION IN MODERN INDIA

Sati practise died out in the nineteenth century, when India fell under British authority. Raja Ram Mohan Roy made the most significant contribution to the elimination of sati in 1811, when he witnessed his brother’s death and seen his brother’s wife burn herself on the funeral pyre. Raja Ram Mohan Roy was appalled by the practise and determined to oppose it; he was the first Indian to petition for the abolition of sati pratha and worked tirelessly to educate people about the sati system. Finally, in 1829, Lord William Bentick made Sati illegal by law.[16] According to this regulation, the Sati ritual was made illegal and punished as culpable murder, bringing Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s mission to a close. Huge changes have happened in Indian culture, and Hinduism is being scrutinised. It might be considered a watershed point in India’s social history. Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s contributions in this area have earned him the moniker “Father of Indian Renaissance.”

Despite the government’s prohibition of sati, society has a great yearning for it, which causes friction. Despite this, sati is still widely practised in India. Roop Kanwar, a widow, was forced into her husband’s funeral pyre to practise sati on September 4, 1987. Despite her protests and attempts to leave, others surrounding her forced her back onto the funeral pyre, where she died. Roop married a guy from the northern Indian village of Deorala when she was just 18 years old. The perpetrators of Roop Kanwar’s death were apprehended, but Roop Kanwar became a goddess, and a temple was constructed in her honour.[17]

In 2008, a 71-year-old widow in Chattisgarh, India, happily practised sati. When her husband’s body was nearly burnt, she dressed herself in a new gown and leapt into the funeral pyre, according to witnesses. Many people were astonished to find that this behaviour was still going on in the twenty-first century, despite the fact that it was unlawful and against Indian law. This case shows how such heinous acts might occur in rural India. This was just one recorded Sati episode, and there are numerous unreported Sati instances all throughout India that we are unaware of, even in the twenty-first century.[18] Another incident was the case of “Kuttu Bai (65) in 2002 in the state of Madhya Pradesh”, “Vidyawati (35) in 2006 in Uttar Pradesh, Janakrani (40) in 2006 in Madhya Pradesh”.

2.6 “CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN (CEDAW)”

Stripping, molestation, kidnapping, rape, abduction, domestic abuse, wife battering, dowry death and harassment, cruelty to women causing them to commit suicide or female foeticide, and Sati. These are all examples of violence against women. On December 18, 1979, the United Nations General Assembly approved the “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)”. The Convention went into effect in 1981. It consists of a prologue and 30 paragraphs that define what constitutes discrimination against women and lay out a national action plan to eliminate such discrimination. A few years ago, India adopted the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Today, sati is classified as a crime under India’s penal code, and those who commit it face a mandatory life sentence.[19]

2.7 IMPACT OF SATI PRATHA ON SOCIETY

It was thought that if a widow performed sati, she would bring honour and prestige to her family and the inhabitants of the village. The family gains social standing and becomes sacred. Sati was also a method of increasing corporate profits. By executing religious events, Brahmin priests obtain wealth, honour, and respect. Many people visit the site of sati practise since it is regarded a holy spot, resulting in significant profits for immediate family, local businesses, and transportation firms. Visitors purchase snacks, incense, and coconuts as offerings, and at the annual fair, they gather money as offerings. The village where sati was performed was considered a pilgrimage site, so people visit it on an annual basis, benefiting traders and priests, bringing in more money and increasing labour demand. Due to her devotion to her spouse, the widow practising sati was deemed a goddess; consequently, visitors offered donations for goddess worship and temple construction, and after the temple was finished, people visited the sacred location on a regular basis. Sati is not widespread in today’s society, but it hasn’t been fully eradicated; once a year is enough to keep this philosophy alive. People typically argue that the priest and corpse should be imprisoned for assisting suicide or doing a sati abolition act. However, the case was dismissed owing to a lack of evidence, and despite the fact that many people observed the occurrence, no action was taken. When female ministers spoke out against the sati, neither the government nor society responded. Many politicians and government figures support sati and contribute at the cite. These terrible practises can be eliminated only if state leaders and the government take the matter seriously.[20]

2.8 INDIAN CONSTITUTION AND PROHIBITION OF HARMFUL TRADITION AGAINST WOMEN

“Gender equality is a value contained in the Indian Constitution’s Preamble, Fundamental Rights, Fundamental Duties, and Directive Principles. The Constitution not only guarantees women’s equality, but also authorises the state to implement measures of positive discrimination in their favour and prohibit all harmful tradition which were followed against women in the name of ritual. Among other things, Fundamental Rights promote equality before the law and equal protection under the law; forbids discrimination against any citizen on the basis of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth; and guarantees equal opportunity to all citizens in employment affairs. Articles 14, 15, 15(3), 16, 39(a), 39(b), 39(c), and 42 of the Constitution are particularly relevant in this context.”[21]

- The State is required to make any specific provisions for women and children-

(Article 15 (3)).

- The State should direct its policies toward ensuring equal rights to an adequate means of subsistence for men and women (Article 39(a)), as well as equal compensation for equal labour for both men and women (Article 39(d)).

- To foster unity and a feeling of shared brotherhood among all Indians, and to condemn behaviours that are detrimental to women’s dignity (Article 51(A) (e)). Here it’s included all type of inhuman practice which should be prohibited against women such as domestic violence, sati pratha, dowry death, harassment and disrespect on the basis of gender

- Reservation of municipal chairperson positions for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and women in such a way as the legislature of a State may prescribe by legislation (Article 243 T (4))

3.1 CONCLUSION

Similar incidents of people being burned in fire for the sake of love may be found in various religions such as Islam and Christianity. It appears that the genesis of sati is quite similar to that of Abraham, known as Ibrahim, who was recognised as the prophet’s messenger who was thrown into the largest fire mankind had ever experienced and emerged unscathed. The flaming furnace is a biblical tale. When three young men refuse to submit to a God other than their own, they are thrown into a fire and burnt alive. Their faith saves them, and they escape the inferno uninjured. As we can see, this is a narrative that exemplifies the strength of faith, trust, and love for God.

People dying of love and faith of their own free will are admirable, but in India, women are either physically tortured by society or medically pressured by religion to join the sati cult. Despite the fact that Muslim monarchs, the British administration, and, more recently, the Indian government have all prohibited sati, the practise persists to this day. Many factors contributed to the fact that sati could not be completely abolished, including religious beliefs, cultural pressure, holy ceremonies, and a lack of information. Even today, sati is done, despite the fact that it is prohibited; hence, why do people not resist it? The answer is very simple first it has been so much blended into Indian society that it has become a normal practice for them and second they think of it as a religious practice. Nobody thinks it’s strange, and the widow accepts it as a way of life. It is not out of love for her spouse, but out of the Indian society’s instillation in her heart. Instead of prohibiting sati, the government should aim to create a societal shift in which people despise such acts. More and more awareness is required in this area if we are to save the lives of innocent ladies in the coming years.

In most civilised countries or societies, sati is deemed murder, however in big India, murdering a woman is considered religious activity. Some scholars believe it is a choice act, while others believe it is mandatory. Personally, I believe that if the conduct is voluntary, it is suicide, and if it is necessary, it is murder. In India, the day Roop Knwar died was referred to as a ceremony, but it was clearly a horrible murder. Many times, Indian men have exploited religion to subjugate women. Now, more than ever, societal awareness is required. People, regardless of religion, need to know what is wrong and what is right. Obviously, mankind is at its pinnacle and highest level. To support humanity, one’s religion must be patient, tolerant, and peaceful. Thus, a religion devoid of mercy, love, and compassion is like to sailing on an empty ship.

[1] Samskaras or sanskaras are mental impressions, recollections, or psychological imprints in Indian philosophy and religion.

[2] “A Socio-Legal Examination of the Sati Tradition – Widow Burning in India.”

[3] Adiga, Malini. “Sati and Suicide in Early Medieval Karnataka.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 68 (2007): 218-28.

[4] Taittariya Samhita- sati adhyay

[5] Jarman, “Sati: From Exotic Custom to Relativist Controversy,”

[6] Jorg fisch,”dying for death: sati in universal context,” journal world history, 16,no.3(2005):318 ‘’

[7] ‘’Sophie M. Tharakan and Michael Tharakan, “Status of Women in India: A Historical Perspective,” Social Scientist 4, no. 4/5 (1975): 120’’

[8] Rigveda, 10.18:7

[9] Garuda Purana, 1.107:29, 10:42

[10] Mahabharata, Adi Parva, 1:125

[11] Devi Bhagavatam, 6.25:35-50

[12] Vishnu Purana, 5:38.

[13] Brihaspati smriti, 24:11

[14] Nani Gopal Chaudhuri, “The Sati in Hyderabad,” complete analysis , Vol. 16 (1953): 342-243

[15] Chaudhuri, “Sati as Social Institution and the Mughals,” 219-222

[16] Fisch, “Dying for the Dead: Sati in Universal Context,” 294

[17] Ahmad, “Sati Tradition – Widow Burning in India: A Socio-Legal Examination,” 4

[18] Ahmad, “Sati Tradition – Widow Burning In India: A Socio-Legal Examination,” 3

[19]“ Jörg Fisch, and the Task of the Historian, Journal of World History 18, No. 3 (2007): 361”

[20] Jarman, “Sati: From Exotic Custom to Relativist Controversy,” 13.

[21] Indian polity- M. Laxshmikant fundamental rights and DPSP (6th ed)

Visit us: https://lawogs.co.in

Join our telegram group:- https://t.me/lawogs

Very well written & got to know a lot from your research article.

Thank you for providing such a good content. Really it’s very nice & helpful for me.